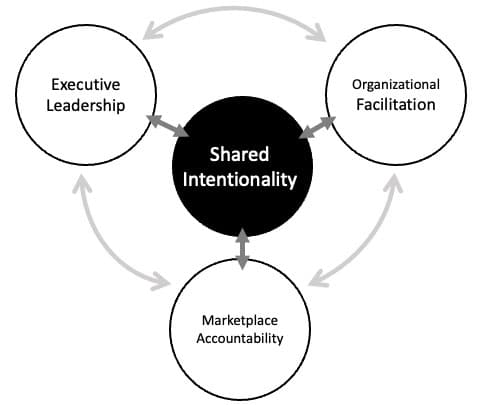

Reflecting on my company’s performance and growth trajectory over decades of organizational evolution, and considering current teachings and philosophies on organizational culture, I envisioned a more comprehensive model of culture. In this newly envisioned culture model, I link a culture pillar to each of the three domains of an organization: the principal executive (CEO), the organization itself, and the marketplace. The three culture pillars linked to these domains are “executive leadership,” “organizational facilitation,” and “marketplace accountability.”

Each of these cultural pillars has its own internal mechanisms for optimization, and the overall organizational culture depends on the integration of these pillars. Executive leadership refers to the leadership provided by the CEO or principal leader over an organization or business unit. Organizational facilitation is the mechanism for discovering, developing, and communicating values and purpose. It is the establishment of ‘internal flow’ and the pillar of organizational health. Marketplace accountability refers to an organization’s ability to hold itself accountable for delivering differentiated value to the marketplace – business’s core purpose. In the culture model, each of these pillars has its own internal structure and mechanisms that enable it to perform and integrate with the other pillars. The overall effectiveness of the culture is dependent on the model’s integration, where the whole is greater than the sum of its parts.

This article is a summary of only the ‘Executive Leadership’ pillar of my three-pillar culture model. The Executive Leadership pillar, as described in this article, is observational and emerges from reflection on my company’s historical performance, as well as a study of existing leadership models and theories. It represents practitioner-derived insight and not formal academic research. Its uniqueness lies in its focus on the mechanisms through which influence occurs rather than on how it is derived. This approach to leadership is more pragmatic and practical for workplace application. The model is motivated by the evolution of leadership in my company and my observation that the leadership models I’ve studied have failed to fully capture my personal experience as an entrepreneur and CEO. Furthermore, my experience in studying leadership models suggests that while many of the models I’ve studied effectively model leadership, not all effective leadership is modeled. In essence, there are often exceptions or outliers that remain unexplained. These models are valuable but insufficient. Many of the models conflate desirable leadership with effective leadership.

Through introspection within my company, interviews with Founders and CEOs, biographical and instructional readings, and academic articles, I’ve observed various sources of leadership power. By leadership power, I mean the capacity to influence. In this context, power is a source of leadership effectiveness. In my model, four primary categories of leadership serve as sources of leadership power. The observation that leaders have disparate leadership styles that transcend leadership effectiveness is explained by category differentiation.

Sources of Leadership Power

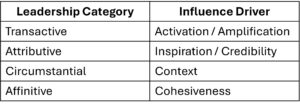

This leadership model considers four categories of leadership from which leaders can draw leadership power – the capacity to influence. I’ve labeled these categories Transactive, Attributive, Circumstantial, and Affinitive:

Transactive Leadership: Leadership power is drawn from the work-related interactions between the leader and subordinate. The specific power is embedded within the interaction itself. These interactions are transactive because they influence the value the business ultimately adds to its marketplace. All of these interactions ultimately serve this purpose. In transactive leadership, leadership power is derived from interaction rather than from the circumstances or conditions surrounding it.

Attributive Leadership: Leadership power is drawn from the attributes of the leader, independent of changes in interactions. Here, we can consider qualities such as work ethic, courage, vision, passion, integrity, and many others.

Circumstantial Leadership: Leadership power is drawn from circumstances within the environment in which the organization operates. Examples of circumstantial leadership are an economic crisis, a competitive threat, a societal need, or an environmental threat.

Affinitive Leadership: Leadership power is drawn from personal affinities between the leader and subordinates. These affinities may be unrelated to organizational objectives, or the organization’s core purpose. Power is drawn from shared personal beliefs, values, and intrinsic relatability.

The test for each category is whether strengthening it increases overall leadership effectiveness while the other categories remain constant. This increased contribution to overall effectiveness demonstrates a category’s validity as an independent power source and shows that the categories are most powerful when integrated. For example, in the Circumstantial Leadership category, it may be unlikely that a particular circumstance will provide any leadership power independently of the interactions in the Transactive Leadership category. However, a change in the Circumstantial Leadership category may amplify the baseline or existing leadership power in the Transactive Leadership category, independent of any changes in the interactions that constitute transactive behavior. The precise, unchanged interaction may provide more or less leadership power only as a result of changing circumstances, not of a changing interaction. This distinction is vital because the issue of independence and interdependence between categories is complex and nuanced.

Consider an example in each of the categories. For Transactive Leadership, transitioning from a reactive to a deliberate interactive style can enhance leadership effectiveness. In the Attributive Leadership category, a greater passion for business goals, a stronger work ethic, or more courageous decisions can enhance leadership effectiveness. For Circumstantial Leadership, an existential threat in the marketplace can improve leadership effectiveness. And finally, for Affinitive Leadership, engaging in an off-site exercise that fosters vulnerability and transparency can enhance leadership effectiveness.

In each of these examples, overall leadership effectiveness is improved from a change in one category, independent of changes in the other categories – although it may be any of the other categories that are empowered by the change.

Category Differentiation

The relationships between leadership categories are complex and nuanced. A consistent challenge to the concept has been that the categories are not distinctive, not clearly defined, and too often overlap indistinguishably in real applications. My response to this challenge is that a distinction should be made between interdependency and indistinguishability. The categories are very interdependent and require integration to optimize effectiveness. They are also distinct and can be distinguished from each other. This concept is perhaps better understood by identifying a primary driver of influence in each. These are as follows:

In this table, we see the distinctiveness of the categories. Does the leader transact or interact with her employees in an interactive style that activates a constructive response and amplifies the other categories? This interactive style would be deliberate, non-reactive, and compassionate. Does the leader have attributes that inspire or establish credibility? These may include work ethic, resume, integrity, and vision. Does the business operate in a set of circumstances that provide context that contributes to meaningfulness or purpose for its employees? This might be a societal need or a competitive threat. And finally, are there affinities that present as shared ideals, values, and beliefs that foster cohesiveness between a leader and her employees? This may mean a collective higher purpose for the business or the contribution it makes to society, separate from the value of its deliverables.

Additive and Subtractive Elements

Aiding the practical application of the four leadership categories is understanding that each source or category has both additive and subtractive elements. For our purposes, we cite a few of these. For the Transactive Leadership category, we reference the work of researchers Robert J. Anderson and William A. Adams, as outlined in their book, “Mastering Leadership.” Based on many years of research, they demonstrate that reactive leadership is subtractive to leadership effectiveness. For executives, transitioning from reactive to deliberate leadership interactions changes these transactive interactions from subtractive to additive.

Similarly, for the Attributive Leadership category, unchecked emotional empathy can be a subtractive attribute. (In my experience, this is a delicate area where treading lightly is prudent. A few years ago, I made a presentation on conscious leadership to a group of young, upstart entrepreneurs. I invoked the framework discussed in this article. The suggestion that emotional empathy could be subtractive to leadership effectiveness was not well received by this young, idealistic audience. The assertion was vociferously challenged, and all else in the presentation was lost to the issue.)

This isn’t to say that leaders shouldn’t care about their employees – they absolutely must care. It is helpful to make a distinction between emotional empathy – feeling what you feel, and cognitive empathy – understanding what you feel and why. Paul Polman, the former CEO of Unilever, and Jacqueline Carter, the Managing Partner at Potential Project, share this perspective. Both have argued that emotional empathy can be a barrier to action. My experience is that while the humanistic quality of emotional empathy is admirable, when unchecked, it can cloud the objectivity needed for effective leadership, in addition to becoming a barrier to action. Both of these effects are subtractive.

As leaders, we can move from subtractive to additive by transitioning from emotional empathy to cognitive empathy, or, I prefer, rational compassion. If we view empathy as an attribute and compassion as a behavior, this transition removes a subtractive element from the Attributive Leadership category and provides an additive component in the Transactive Leadership category.

A subtractive risk for Circumstantial Leadership power results from disingenuousness or embellishment. Leveraging a circumstance by catastrophizing, exaggerating a threat, or overstating a company’s ability to address or remedy a societal need can yield short-term leadership benefits. However, over the longer term, these practices, which may be additive in the short term in the Circumstantial Leadership category, will be subtractive in the long term in the Attributive Leadership category – most notably subtracting attributes such as authenticity and integrity. In this scenario, the company trades longer-term benefits for short-term benefits.

Subtractions in the Affinitive Leadership category pose disproportionate risks for leadership and organizations. Some affinities can obscure objectivity in ways that are subtractive for leadership effectiveness. We are sometimes at risk of building a C-suite or developing management teams with people who are similar to us in comfortable but unhelpful ways, while overlooking key strengths that are helpful for organizational health and strategic growth. In my company, when we hired key decision-makers anchored in values, character, and talent—and evaluated candidates against clear role criteria—we built an extraordinary C-suite and leadership team that was also very diverse. Not allowing affinities to obscure objectivity provided for measurably improved, durable, persistent returns.

Breaches of ethics, absences of moral conscience, or malfeasance, if present, are clearly subtractive in the Affinitive category. Conversely, higher purpose initiatives are potentially additive elements in the Affinitive Leadership category. More information on this topic is provided later in the article.

A Simple (but Incomplete) Framework

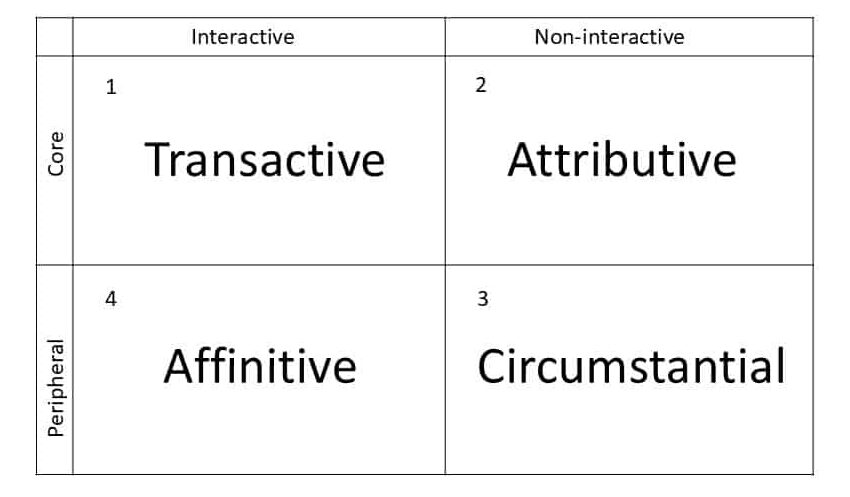

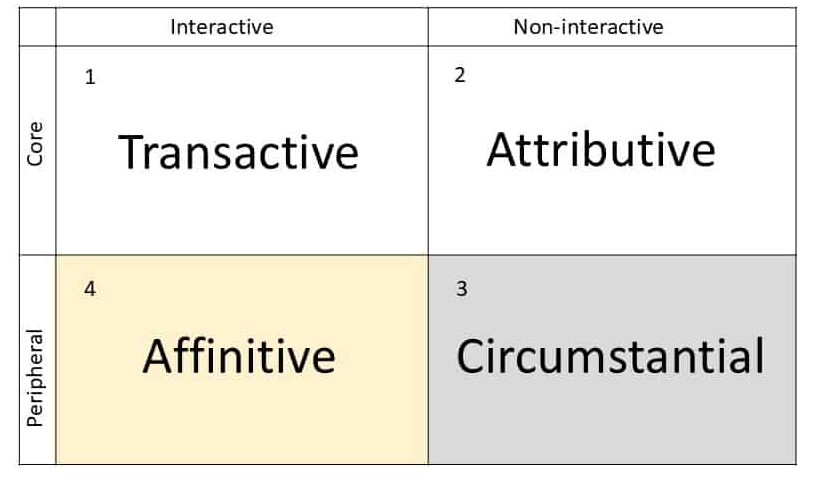

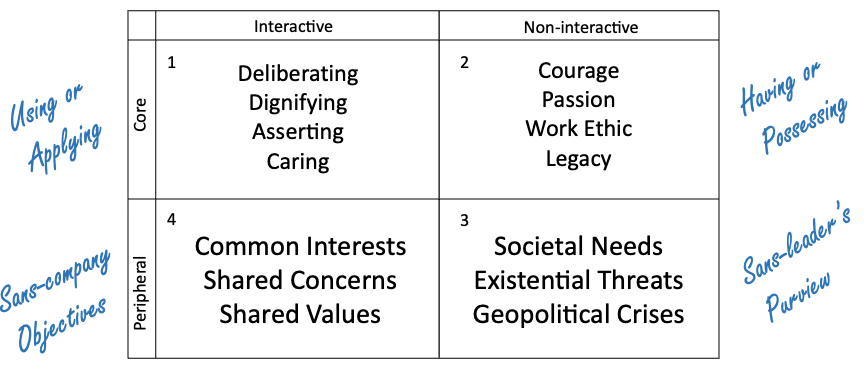

Utility is often eroded by complexity. To provide utility for an enterprise use of the model and a framework for integration of the categories, I present the model simply (but incompletely), along two dimensions:

Leadership Quadrants

Here, I am positioning the leadership categories from which leaders draw power along the dimensions of peripheral to core aspects (the Y-axis), and from interactive to non-interactive influences (the X-axis). Defining the Y axis, aspects core to business leadership are those within the leader’s purview and relevant to the business’s goals and objectives. Aspects peripheral to business leadership are those outside the leader’s control or the business’s goals and objectives. Defining the X axis, interactive influences provide leadership power within the interaction, while non-interactive influences provide leadership power outside of it.

Consider quadrant 1 (Transactive) as ‘using or applying’ and quadrant 2 (Attributive) as ‘having or possessing.’ Quadrant 3 (Circumstantial) is ‘outside of the leader’s purview,’ and quadrant 4 (Affinitive) is ‘unrelated to company objectives.’

For additional clarity, here are a few of the many items that may appear in each quadrant:

This framework straightforwardly presents the model, facilitating a visual understanding of the integration opportunities. Quadrant 4 is specifically interests, concerns, and values that are not relevant to the organization’s goals and objectives.

Although it sufficiently provides utility and simplifies a complex model, the grid, as presented, is incomplete. Presented along these dimensions, there are two deficiencies. The grid excludes internal company circumstances, considering only external or environmental circumstances. These excluded internal circumstances are non-interactive, but they are, nonetheless, relevant to the company’s goals and objectives. I think of these as ‘facilitated’ circumstances, or perhaps internal conditions. They include items like core purpose, company values, and performance results. The second deficiency is that the Affinitive Leadership category, as presented in the grid, excludes intrinsic identity and relies solely on affinity-based interactions. Despite these deficiencies, this framework is simple and valuable as a basis for developing leadership power, serving as a template for category integration.

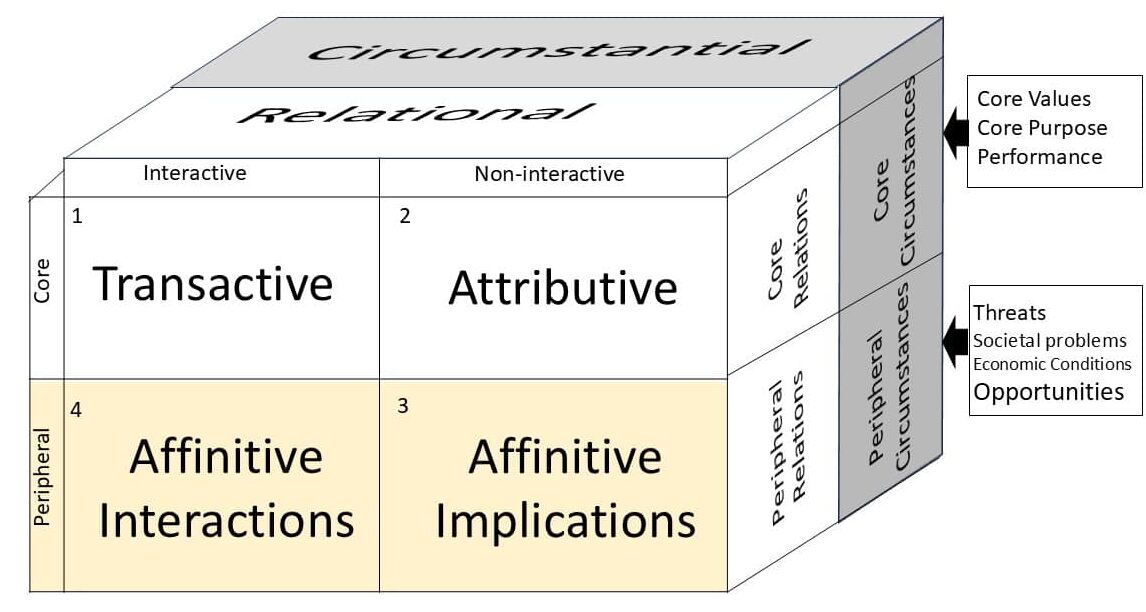

A Complex (but more complete) Framework

Again, acknowledging the erosion of utility by complexity, here is a less useful but more complete iteration of the leadership framework:

3 Dimensional Iteration

To address the deficiencies of the two-dimensional grid, completing the framework requires adding a third dimension. In this more complex framework, ‘Circumstances’ move to a back tier and are divided between Core and Peripheral. The Core Circumstances are mainly facilitated – they fall within the leader’s purview and are relevant to the company’s goals and objectives. They constitute the internal environment of the company, or the internal circumstances or conditions under which the leader operates. Examples are the internal values of the organization, its core purpose and mission, and company performance or results. These internal circumstances are a key point of integration in the upper core quadrants, and greatly amplify leadership power when properly integrated.

The Peripheral circumstances are primarily what we already consider in quadrant 3 of the simple, two-dimensional framework. However, these now move to the back tier in the Peripheral (lower) portion of the grid. These are the circumstances that constitute the external environment in which the company is operating. Included here are threats and opportunities that exist outside of the company in the marketplace. Here, the company may address a societal issue, mitigate an environmental danger, or respond to a direct threat from a competitor.

In the forward tier of the grid, we break apart the Affinitive quadrant to separate implicit, non-interactive affinities, which are primarily rooted in personal identity and personal values. The interactive portion of Affinities is now only affinity-based interactions. These are non-transactive interactions, but contribute to leadership effectiveness. An example in the Affinitive Interactions quadrant is the company’s off-site, where affinities that provide leadership power are built or discovered through bonding exercises that foster transparency and vulnerability.

Integration of Leadership Categories

As mentioned earlier in this article, the leadership categories are interrelated, and changes in any one category will affect the others. By recognizing leadership within this quadrant framework and understanding which quadrants leaders draw power from, leaders can engage in activities and practices to strategically integrate the quadrants. By integration, we mean that the total of the quadrant items working together across quadrant boundaries is greater than the sum of their individual contributions. This cross-boundary fit is integral leadership. It is how the most effective leaders amplify their leadership power. Instead of a collection of individual leadership skills, the grid quadrants become an integrated system of leadership. We should consider strategic quadrant integration to be the quality of fit between quadrant items across quadrant boundaries. How the items within and between quadrants fit together determines the amount of amplification from quadrant integration. The simpler two-dimensional, four-quadrant grid lends itself to designing and executing a quadrant integration strategy.

With this understanding of quadrant integration, leaders can strategically facilitate or accelerate it to improve leadership effectiveness. A profound opportunity to accelerate leadership effectiveness lies in the Transactive quadrant, specifically in the difference between reactive and deliberate managerial styles. Suppose a leader with a reactive style can transition to a deliberate style of interactivity in the Transactive quadrant. In that case, this transition within the Transactive quadrant amplifies leadership power in the Attributive and Circumstantial quadrants. Deliberation makes better use of attributes and circumstances than reactiveness can. Similarly, items in the Attributive or Circumstantial quadrants can amplify the value of deliberation in the Transactive quadrant.

My experience suggests that contemplative practices, such as mindful meditation, help facilitate these transitions and foster the integration of leadership quadrants. A substantial body of research demonstrates that meditative practice is highly effective in promoting a transition from a reactive to a deliberate interactive style. The practice also cultivates Systems Intelligence—an intuition for the value of interrelatedness that enables understanding of the value of fit for amplification—the essence of integration.

Although this paper focuses on the ‘executive leadership pillar’ of the larger culture model, it is worth noting that an opportunity for quadrant integration also exists in the Organizational Facilitation culture pillar mentioned in the opening paragraph. Here, organizations can utilize assessments to discover complementary quadrant strengths for their key decision-makers. They can leverage organizational health to integrate quadrants across the organization. As a Founder, I drew disproportionately from the Attributive quadrant (often at the expense of the Transactive quadrant), so hiring other executives and key decision-makers who could complement my Attributive strengths with strong interactive Leadership skills in the Transactive quadrant was critical to effectively integrating the leadership quadrants.

At a defining juncture in scaling within my company, the organization benefited from executing within both pillars, Executive Leadership and Organizational Facilitation. As an executive leader, I began practicing mindful meditation, which improved my interactive skills in the Transactive quadrant. With these improved interactive skills, I could integrate multiple quadrants and derive an overall leadership benefit greater than the sum of the individual quadrants. My experience was that my transition to less reactivity and more deliberation in the Transactive quadrant amplified the attributes (already present) in the Attributive quadrant and enabled more empowerment from circumstances in the Circumstantial quadrant. At the same time, in the Organizational Facilitation pillar, we achieved integration of the quadrants by hiring and appointing new, highly talented key decision-makers with strong interactive skills in the Transactive quadrant that complemented my strengths in the Attributive quadrant.

The three-dimensional model, while more complex, demonstrates meaningful integration opportunities in the third dimension. Again, at my company, when we developed new internal circumstances through the professional facilitation of a robust organizational health initiative aimed at discovering the company’s core purpose and core values, leadership effectiveness improved in both the Transactive and Attributive quadrants. When we anchor transactional interactions to a distinctive set of core values or a clear core purpose, leadership effectiveness improves. When we integrate leader attributes with the company’s values and purpose, leadership effectiveness improves.

Another key integration point utilizing the third dimension is company performance. Without question, and all else being equal, leadership effectiveness improves as company results improve. The company results are an internal circumstance that empowers the Attributive and Transactive quadrants.

Leading with Higher Purpose

A higher purpose and moral conscience can enhance leadership effectiveness in the Affinitive Leadership category (quadrant 4). This improvement in the Affintive Leadership category presents an opportunity for amplification across all categories, resulting in a level of effectiveness that exceeds the sum of the individual leadership categories or quadrants.

I teach my students that the core purpose of business (collectively) is to add value to the marketplace. It follows that the core purpose of a company (individually) is the unique or distinctive way it adds value to its marketplace – or the unique and distinctive (differentiated) value it adds to its marketplace.

I believe that companies should grow from a commitment to purpose rather than merely seeking financial gain. However, the commitment to purpose must translate into differentiated value for the marketplace. A company must differentiate itself.

For core purpose, we define value as the differentiated benefit of the deliverable that people are willing to pay for. This definition is crucial as it serves as is the purest measure of a company’s sustained viability. Without doing this, businesses can do little else. At the same time, I describe core purpose alone as ‘insufficient.’ Company leaders must also facilitate higher purpose initiatives and values in their organizations. While core purpose provides differentiated benefit as value to the marketplace, higher purpose provides affinity value to the marketplace. The total value brought to the marketplace includes both the differentiated benefit of core purpose and the affinity value of higher purpose.

The conscious business community often argues that there should ‘necessarily’ be no distinction between core purpose and higher purpose – that they are the same. I’ve debated this, disagreeing with the assessment. There can be no distinction, but this depends on the circumstances of the industry, company, and the deliverable. The leadership categories in this quadrant framework offer a deeper understanding of the value of a company’s higher purpose, which can be distinct from its core purpose. Utilizing the three-dimensional framework presented in this article, core purpose resides in the upper quadrants, and higher purpose resides in the lower quadrants. Core purpose contributes to leadership power through upper-quadrant integration. Higher purpose contributes to leadership power through lower-quadrant integration.

Research demonstrates that companies that engage in higher-purpose causes and initiatives, demonstrating moral conscience, can experience improved company performance, even if the higher purpose is separate from and distinct from the company’s goals and objectives (the lower quadrants). This enhanced performance is attributed to the moral conscience within executive leadership. It serves as a testament to the additive power of leadership in the Affinitive Leadership category. Here, there is a natural humanistic affinity for this type of leadership that can be distinct from, and separate from, the company’s goals and objectives. Higher purpose being a moral obligation for business, while simultaneously yielding higher performance, is evidence of an organizational (and marketplace) affinity for higher purpose. In summary, while the Affinitive Leadership category has the potential for subtractive elements, it can also serve as a powerful amplifier in the context of quadrant integration when company leadership embraces higher purpose as an expression of moral conscience.

Concluding Thoughts

The modeling of leadership, as described in this article, is motivated by my personal experience as a business Founder and entrepreneur, and my observation that many existing leadership models are inconsistent with that experience. For me, the framework within this article brings value to the discussion in the following ways:

- It demonstrates that leaders can lead in different ways, drawing power from different leadership categories. This diversity in sources of leadership power helps explain the exclusions and exceptions that are unaccounted for in many leadership models.

- It helps create an understanding of the need for Founders and entrepreneurs as business leaders to develop skills in the Transactive Leadership category as a pursuit of overall leadership effectiveness.

- It provides a visual for category (or quadrant) integration, along with an understanding of amplification across quadrant boundaries.

- It helps explain the synergies and interrelatedness between moral conscience and shareholder value and provides a rationale for higher purpose for business.

Much of the current narrative on leadership conflates desirable leadership with effective leadership. As much as we would like it to be, these are not necessarily the same. Business leaders can effectively lead in different ways, drawing leadership power from each of the four categories of leadership described in this article. Although my experience is observational, different leaders have natural leadership styles that draw disproportionately from one or more of the categories. Founders and entrepreneurs more often draw power disproportionately from the Attributive category, and in ways that are sometimes subtractive from the Transactive category. Professional CEOs and managers more often draw power from the Transactive category, and in ways that amplify the Attributive category.

In my company, when we integrated quadrants – both intra-personally and organizationally – the results were profound. The path to leadership effectiveness is not to pigeonhole leaders or leadership into a single category, as many models do – but rather to work toward category integration, where the fit of the items across category boundaries will create a whole that is measurably greater than the sum of its parts, the result being an integral optimization of leadership effectiveness.