The debate between advocates for shareholderism and those for stakeholderism is perplexing. Should the prism through which we run our businesses be profit first? Or should it be people or purpose first? Should we be in the Ayn Rand / Milton Friedman camp? Or should we be in the John Mackey / Raj Sisodia camp? Is an imposition of ESG on shareholders socially responsible? Or is it ethically bereft?

I was indoctrinated into the Atlas Shrugged culture early in my professional career and became an evangelist for its principles. ‘If we take care of our shareholders by optimizing profit, the stakeholders will benefit.’ Therefore, profit was a moral obligation. This perspective was foundational for many years in running my company.

But then, late in my tenure, I embraced contemplative practice (mindful meditation). Over an extended period in practice, my perspective changed. With an emerging empathy – and then compassion, the company started putting people and purpose ahead of profit. With this culture shift, great things happened. Although the company had a long track record of success, with this transformation, it entered a magical period of broader success across a multitude of measures. At the core of the success was attracting and retaining highly talented employees, improved engagement across the company, and alignment of values and objectives. The attraction of intellectual capital accelerated progress.

The continually improving metrics as an outgrowth of improved culture were self-reinforcing. Convinced I had found the magic sauce for business success, I shifted my perspective to advocacy for stakeholderism. I was as confident in stakeholderism as I was twenty-five years earlier in the value of shareholderism.

I listen to both sides of the debate. I listen to John Mackey debate Yaron Brook from the Ayn Rand Institute. I listen to Raj Sisodia advocate for Stakeholderism and then I read highly informed and well-written opinion pieces in the Wall Street Journal1 that make a convincing case against Stakeholderism and advocate for the Milton Friedman perspective of Shareholderism. I reflect on my own experience of accelerated success as my company culture shifted from shareholderism to stakeholderism. And with more information, I find that I am increasingly moving from a binary perspective of the principles to a melded perspective that challenges the distinction.

The more I read and listen to each side of the debate, the more I question whether each group is arguing opposites sides of the same issue or whether there is a conflating of very different issues – not the same at all.

The transformation to a stakeholder orientation in my company was emergent. It was not strategic. The emergence was an occurrence from my leadership position as a founder combined with my newfound personal contemplative practice. With practice, my worldview changed. This change was a change of heart. The shift in orientation to the stakeholders came naturally. It was authentic. Perhaps the authenticity is why it was remarkably transformative for the organization.

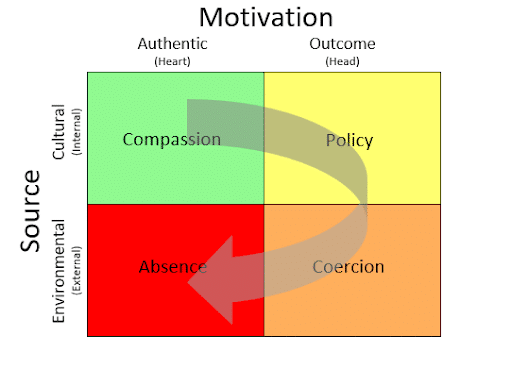

When assessing a shift to stakeholderism, we should distinguish between sources and motivations rather than painting with a broad brush. Is the source cultural or environmental? Is the motivation authentic (heart) or outcome-based (head)? A cultural shift toward the stakeholders originates from inside of the organization – from the company’s culture. An environmental shift toward the stakeholders is imposed from outside the organization – from the company’s environment. These are not the same.

An authentic motivation for a shift to the stakeholders is empathy-based and requires the essential conversion of empathy to compassion. We say this is from the heart. An outcome motivation for a shift to the stakeholders is rationally based and is a strategic initiative to generate the desired outcome. Again, these are not the same.

The current narratives paint with a broad brush and don’t make these distinctions. There is an assumption of just two buckets – either shareholderism or stakeholderism. In reality, stakeholderism is not a single bucket. It is a grid with four quadrants, and in each quadrant, stakeholderism manifests differently. Each quadrant can be argued separately against shareholderism.

Reading or listening to the arguments for and against stakeholderism, it seems the advocates and detractors are rarely in the same quadrant. Instead, they may be on opposite sides of different arguments – not the same argument, as we assume.

We derive the first quadrant of the grid from cultural sourcing and authentic motivation. This quadrant manifests in the company as the workplace shifting toward compassion. Moving clockwise around the grid, we derive the second quadrant from cultural sourcing and outcome motivation. This quadrant manifests in the workplace as developing policy.

Continuing to move clockwise, we derive the next quadrant from environmental sourcing and outcome motivation. This quadrant manifests in the workplace as increasing coercion. Finally, we derive the fourth quadrant from environmental sourcing and authentic motivation. This quadrant manifests itself as ‘absence’ – as authentic motivation and environmental sourcing are fundamentally incompatible.

Here, in this model, it is possible to be both – an advocate and a detractor of stakeholderism – depending on the quadrant. Many of the advocates argue quadrant 1, while many of the detractors argue quadrant 3. It is reasonable for an advocate for quadrant 1 to be a detractor of quadrant 3.

Perhaps the distinction between conscious leadership and conscious capitalism requires separating quadrant one from the balance of the grid. It is here with conscious leadership – in quadrant one that the magic happens.

Although the proliferation of the terms is relatively new to the business lexicon, the ideas are not. We used to talk strategically about trading growth for profit – or profit for growth. Or perhaps brand for profit or profit for brand. The debate was really a discussion about trading short and long-term perspectives. This discussion is similar (if not the same) as the cultural stakeholder discussion. Culturally, the short view favors the shareholder, and the long view favors the stakeholder. A shift to cultural stakeholderism is one of the transitions of maturity that constitute the adolescence of a company. It contributes to durability and better positions an organization to persevere through turbulence.